A visit to the 17th century in a different part of the world

My husband and I recently spent two weeks on St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands, testing whether we could work remotely while enjoying a break from the snow and cold. I’m delighted to report the experiment was a success!

We last visited St. John thirty-some years ago when we were dating and had always promised ourselves a trip back. One of the many appeals of the island is that a large portion of its territory is in the Virgin Islands National Park. In between working (yes, we did work!), we took advantage and spent time hiking its many trails, snorkeling, enjoying the beaches, and exploring a plethora of Dutch sugar plantation ruins that still stand. I found the island’s history fascinating and heartbreaking at the same time.

Here are a few tidbits I picked up: St. John, originally Sankt Jan, was claimed in 1675 by the Dutch governor of nearby St. Thomas, Jorgen Iverson, and was formally occupied in 1718. Tobacco, cotton, and sugar plantations had existed in the West Indies since the early 1600s (about the time of the Polish Winged Hussars’ dominance on the battlefield) and now sprang up in earnest on St. John.

The plantations, especially ones that grew sugarcane, were labor-intensive, and owners satisfied that need on the backs of slaves. While plantation owners on other Caribbean islands might have also used European indentured servants and white slaves, St. John’s plantations were worked almost entirely by African slaves brought to the island. The initial slaves who arrived with the settlers in 1718 numbered less than twenty, but fast forward a mere fifteen years, and their numbers had exploded.

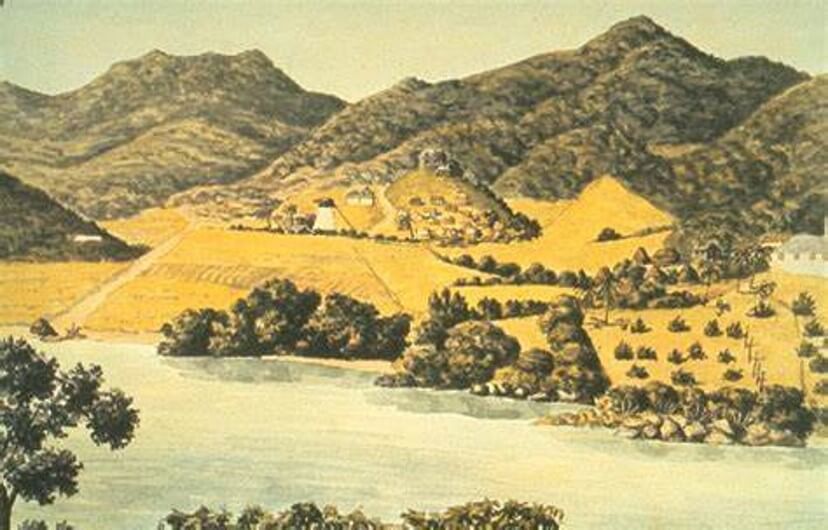

By 1733, St. John had been cleared of most of its timber and held 109 estates, ranging from 6.5 acres to 462 acres in size. One-fifth of those plantations was devoted to raising sugarcane, and the island was populated by over 1,000 slaves—more than five times the European settlers!

It’s hard for me to visualize what the island must have represented to these slaves, especially in the modern day when I, as a tourist, was surrounded by beautiful blue waters and soft tropical breezes that ruffled palm trees. But for a plantation slave, this island paradise was hell on earth.

Tensions between slaves and their overseers built and finally boiled over, culminating with a slave revolt in November 1733. They killed nearly all the soldiers in the island’s fortress and continued with the white overseers and settlers. In one of the earliest and longest slave revolts, they held the island for six months until French marines from Martinique arrived and reinforced the Dutch. Losses were steep on both sides: 300 slaves, or one-third of their numbers, lost their lives along with three-quarters of the European settlers.

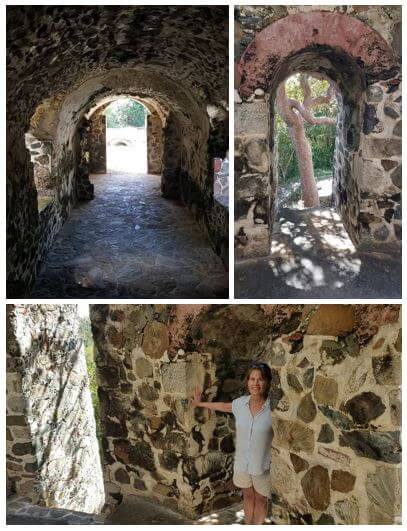

These pictures were taken at some unmarked ruins we happened upon while we were out exploring a winding dirt road. On the bottom, I’m standing in an old windmill, and to my right (left side of the picture) is the chute where the cane juice flowed out. I have to admit an eerily haunting quiet lingered like invisible mists, sharpening a sense of the suffering that once existed on these grounds.

I would love to return for a chance to explore and learn even more about the island’s past.

Leave A Comment