The reasons for military conflicts are often complicated and come in many shades of gray. The Moldavian Magnate Wars that took place at the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s southern border from the late 1590s to the 1620s were no different. The Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire wrestled for control over the buffer territory belonging to Moldavia, but beyond that was the festering situation caused by the constant raiding and counter-raiding between the Tatars, vassals of the Ottoman Empire, and the Cossacks (more about them later).

In the Winged Warrior Series, I spend time portraying the devastation caused by the Tatar raiding parties that would swoop into southern Poland every year and carry off loot and numerous captives. Many of those captives were women and children who would end up being sold off in various slave markets within the Ottoman Empire, Caffa (modern-day Feodosiya) in the Crimea being one of the most notorious.

Depending upon the source one reads, estimates range from one to two million humans that were carried off between the 15th and 17th centuries, leaving vast sections of the Steppe devoid of habitation.

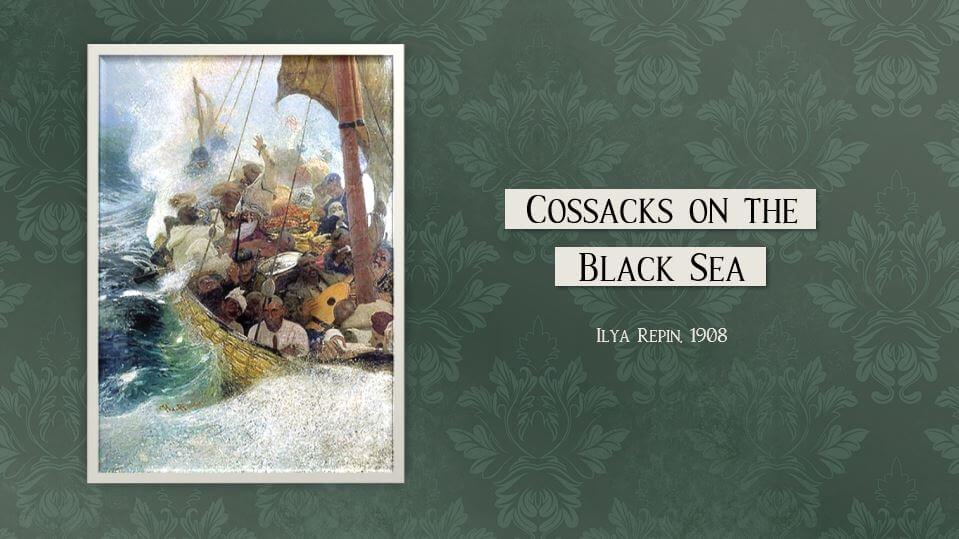

On the other side of that same coin were the Cossack raiders who terrorized Ottoman settlements along the Black Sea coast. They were, in a word, pirates. They attacked from boats designed for speed and stealth

and were quite successful at their own looting and pillaging—so successful, in fact, that fortresses were specifically erected along the coastline to repel them. Those fortifications didn’t always prevent devastation and sometimes became part of the devastation themselves.

Protests from the Ottomans and the Poles resulted in numerous treaties between the two sides, but the raiding continued despite the agreements. One assault would result in a counter-assault, and so the vicious cycle continued, with each side holding the other responsible. The Ottomans would claim they were trying to rein in the Tatars while the Commonwealth insisted the damage was being done by the Don Cossacks—who were not under Commonwealth control—rather than the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who were considered to be part of the Commonwealth (at times more loosely associated than at others).

In various letters penned by commanders of Black Sea forts and ships are descriptions of the vexing problem the Cossacks presented. One author forfeited his life shortly after delivering his report because he had failed to stop the destruction of the fortress under his command.

Whichever group of Cossacks deserves the blame (and perhaps both do), they were bold, ruthless raiders who ventured as far south as Constantinople, where they set fire to an outer suburb belonging to the city.

With the allure of profit and an abundance of audacity on each side, it was no wonder Tatars and Cossacks alike were nearly impossible for the reigning powers to bring to heel.

Leave A Comment