Portret Trumienny

The U.S. is gearing up for Halloween on Oct. 31, and we’re surrounded by images that herald the day, such as pumpkins, ghouls, and coffins. And speaking of coffins … I’ve been wanting to write an article about the 17th and 18th century Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth’s tradition of using coffin portraits, and Halloween struck me as the perfect time to do just that.

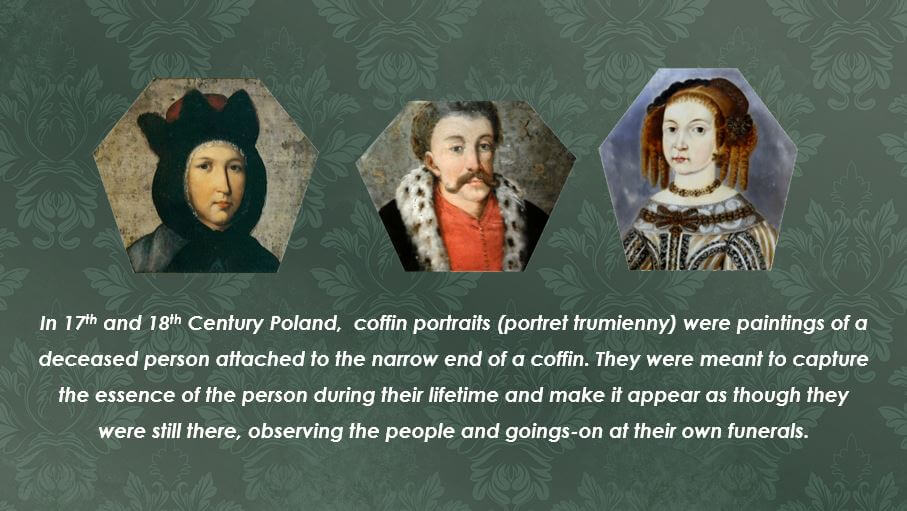

You may wonder what exactly one means when one discusses a coffin portrait (portret trumienny in Polish). In a nutshell, they were images of a deceased person painted on copper, tin, or lead plates and attached to the narrow end of a coffin, where the head would lay. The shape of the portrait mimicked the shape of that end of the coffin, which explains why so many were created in the form of hexagons or octagons, similar to the examples above.

The purpose of this funerary art was to capture the essence of the person during their lifetime and make it appear as though they were still there, observing the people and goings-on at their own funerals. Hence, in many of these portraits, the painting’s eyes seem to gaze right at a viewer.

In order to create this impression, subjects often had their portraits painted while they were alive. They would wear their most luxurious clothing or the regalia that depicted who or what they were during their lifetime. For example, a hussar might wear a fine red żupan under his richly polished armor. In The Heart of a Hussar, Eryk’s wife, Lady Katarzyna, had her portrait painted at a time when disease hadn’t ravaged her. She posed in her finest riding clothes so she would be “dressed to ride” into the afterlife, which was not at all uncommon among the szlachta (the nobility).

And speaking of the szlachta, they were the primary consumers of this postmortem artwork. Not only could they afford it, but funerals were extremely important to them, and they spent lavishly according to their means. Such a showy display was not only an opportunity to honor the dead, but it was also a chance to flaunt their high estate, which the szlachta were extremely fond of doing.

It was not unheard of for a lord’s funeral to last days, even weeks, and be quite an extravagant event. The historian Bernard O’Connor has been quoted as saying of these affairs: “There is so much pomp and ceremony in Polish funerals that you would sooner take them to be a triumphant event than the burial of the dead”.

The coffin portraits were part of the castrum doloris, a structure set up in a church (usually that the deceased had contributed to during his or her lifetime). The castrum doloris held the coffin, along with decorations, candles, coats or arms, and epitaphs—like the castrum doloris (*SPOILER ALERT*) that was erected for Eryk’s funeral in A Hussar’s Promise.

Before the burial, the coffin portrait was removed and hung in the church. Many of these are still on display in Poland today in churches and museums. I remember touring one ancient church during a visit to Poland and being awed by how many of these portraits adorned the walls.

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s poor would also vie for coffin portraits, though their limited means only allowed for paintings done by amateurs and are considered to hold little or no artistic merit.

How lucky we are that many coffin portraits survived. These unique glimpses now provide a wealth of knowledge about many cultural aspects of the Commonwealth’s 17th and 18th century szlachta, including fashion, clothing type, hairstyles, and jewelry. How wonderful it is to have the opportunity to study these “snapshots” of the past!

Leave A Comment