Historical fiction is one of my favorite genres because I can immerse myself in a different time and place, in a world rich with detail that engages all the senses. I can be sitting at a lord’s banquet table bowed with platters of food, in a peasant’s house with a bowl of wild mushroom soup before me, or in a camp where soldiers are munching on stale provisions.

Food was a subject I had a lot of fun researching for my novels. The question might have started with, “What did people eat in Poland in the 17th century?”, but it quickly grew tentacles. What time did they eat breakfast? What did it consist of? What did that breakfast look like for a free farmer? A soldier on the road? A hussar? A traveler in an inn? What did they typically drink with their meals? What did a lord and his lady have for an “everyday” supper? How did that differ from a celebratory banquet for sixteen? What did the staff that ran their household eat?

The answers to these many questions depend upon where one found oneself on the socio-economic spectrum. Unsurprisingly, royalty and the nobility ate better than the peasants. By far the biggest difference was the presence of meat on the table. The peasant (or yeoman or free farmer) who worked his lord’s demesne along with his own plot was not allowed to take meat from his lord’s lands. If he got meat at all, it was through his own livestock (primarily chickens) or the generosity of his master.

While game was served at a lord’s table, it appears to have been more of a specialty. The most common meats, in order, were beef, pork, poultry, and fish.

If one were fortunate enough to be invited to feast at a wealthy lord’s table, what sorts of dishes might one be served? Perhaps “hashmeat in the Cypriot style,” “capon with caviar,” or “Hungarian-style spit-roasted shoulder of venison.” Or all three, if it was a lavish feast! And they were well-spiced. The spices included saffron, pepper, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, and nutmeg in such quantities it was said that foreigners had difficulty swallowing the food. Capers, raisins, and vinegar were also used liberally. Presumably, if we were to climb aboard the time machine and arrive in time for supper, we wouldn’t be able to eat the main dishes! A good excuse to move on to dessert, I say.

Maybe we could tolerate some of the side dishes, which would have been comprised of myriad vegetables and legumes (but not potatoes–they hadn’t made it to Poland yet) in a variety of sauces. Interestingly, sugar was an important ingredient in sauces, including those for meat and fish.

Speaking of sugar, it, along with honey, was also important in desserts. Fruit compote, almond tarts, candied almonds–or something more elaborate, like pears stewed with cucumbers and figs–might be served to punctuate the end of the meal. How about some gingerbread and sponge cakes? Or fried sweets? French pastries were popular as well.

How odd. I’m suddenly hungry.

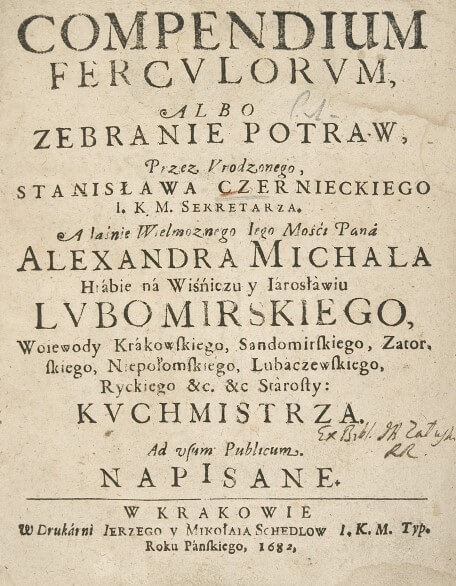

The First Polish Cookbook

Stanisław Czerniecki’s Compendium ferculorum was the first Polish cookbook ever published, and it gives us a wonderful peek into that world. It came out in 1682 and boasts hundreds of recipes (including 16 recipes for chicken soup alone!), chef’s secrets (lots of spice and fat), and advice on side dishes, condiments, and food presentation.

With Easter on the horizon, it seems appropriate to mention meatless dishes for fasting days. I could easily fast if I had the “fast day pancakes,” made with nuts, poppy seeds, and honey. Yum!

Leave A Comment