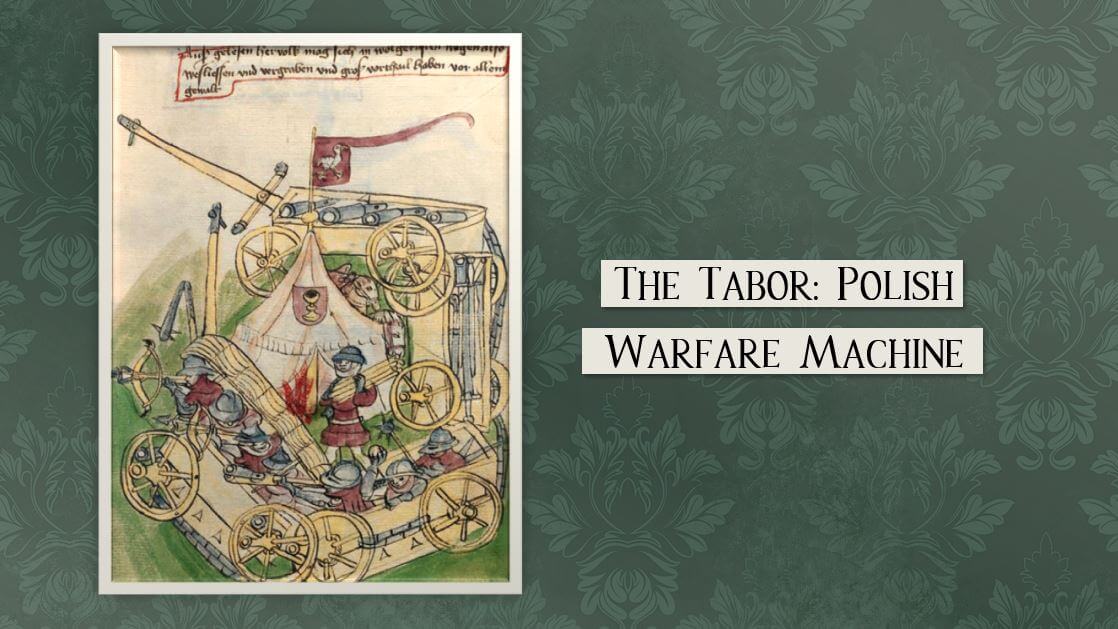

War wagon, war fortress, rolling fortress, rolling stock, stock, wagon fort, or tabor?

Have you ever heard these terms? I hadn’t until I did my research for The Hussar’s Duty, Book 3 in The Winged Warrior Series, and boy, did I learn some interesting facts about this mobile fortress (and that’s yet another term). For this discussion, I’ll try to stick with tabor, which was the label used by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth army, but do forgive me if I slip.

The tabor was a mobile fortification that figured prominently in the Battle of Cecora on September 19, 1620. This machine, however, became even more important during the army’s retreat after their devastating defeat at the hands of a combined force of Ottomans and Tatars. That retreat began 10 days after the battle itself, on September 29, and lasted until the retreating troops were finally crushed on October 6, 1620.

When Grand Hetman of the Crown Stanisław Żółkiewski first set out with his cobbled army to meet the Ottomans on a battlefield just east of Cecora (modern-day Țuțora in Romania), he didn’t expect there would be a clash. He believed that he and the Ottoman commander, Iskender Pasha, would sit down and negotiate. They had done it before. This conflict, however, was different, for a variety of reasons. To name a few, the Commonwealth suffered from bad intelligence, overconfidence, troops comprised largely of magnates’ private armies (too many cooks in the kitchen), and underestimation of the enemy’s strength. The Ottomans would be reinforced by the Tatars, and while their addition didn’t surprise the grand hetman, the size of the Tatar force, when it finally arrived, did catch him off guard. Keep in mind this man was in his early 70’s and suffering from poor health. His condition would factor into the decision-making that doomed the Commonwealth army.

Żółkiewski, in his heyday, was a brilliant strategic commander. In this particular battle, he struck on an innovative plan that harkened back to the Hussite victories in the 15th century and employed the tabor. Some background: The Hussite tabor was an arrangement of wagons in a square. The wagons themselves were equipped with guns and manned by a crew of 35-45 fighting men that included soldiers, artillerymen, crossbowmen, and pikemen. Within the square, surrounded by the armed wagons, cavalry was placed. The wagons were pulled by teams of horses arranged very close together so they nearly touched the back of the wagon before them, creating a sort of impenetrable “chain,” if you will.

Once assembled, the tabor tactic involved two phases: defensive and counterattack. As the enemy advanced on the tabor, they were fired on until they were weakened. Then the counterattack began, with the calvary and infantry advancing from inside the square and engaging the demoralized troops.

Once Żółkiewski acknowledged battle was eminent, he laid out a plan that involved two tabors flanking his main strike force of 5 regiments. The regiments were comprised of Polish hussar cavalry, Cossack calvary, and light cavalry. He decided on the tabors because the battlefield was open, flat ground, where these mobile fortresses were most effective and devastating. Plus, his experience fighting Tatars gave him confidence the method would work.

The scale of Żółkiewski’s formation was massive—at least it seemed so to me! Unlike the smaller tabors used by the Hussites, the Commonwealth’s right tabor was defended by 700 men and the left by 500. According to Ryszard Majewski, author of Cecora 1620, “The shape of the battle formation formed in this way approached a rectangle, with a front width of 1100-1200 meters and a depth of up to 1000 meters” (translated from Polish). That’s between .68 to .75 miles wide and .62 miles deep!

Żółkiewski determined that the most vulnerable parts of the formation were its sides and rear, so he beefed up the troops in these spots in order to close gaps. With the forces thusly arranged, he intended to weaken Tatar assaults and deliver the counterattack with his hussar banners—using the same tactics the Hussites had employed when they defeated their enemies with the tabor. On paper, it was a remarkable plan that gave the Commonwealth army a large dose of confidence.

A plan drawn up on paper is one thing, but the actual battlefield proved to be quite another. For all its brilliance, the scheme held several devastating flaws. The first was that it hampered the cavalry’s mobility. Rather than a wide, shallow formation, it compressed the regiments into tight columns, limiting their maneuverability. The second was that the success of the mission depended upon keeping the formation intact. It worked on the principal of “together we are strong,” and any cracks exposed the entire force to enemy attack.

The battle began at noon on September 19. At first, the Commonwealth experienced success and pushed the enemy back causing much damage. However, the right tabor encountered an obstacle. Some articles report it as a trench, others as a ditch or a ravine. Suffice it to say, it was a depression in the ground that caused the right tabor to swing to the right, thus opening a gap at its rear and exposing the strike force located in the center of the formation. The Tatars had been alert, watching and waiting, and their cavalry swept through the breach as soon as it formed, wreaking havoc on the immobile Polish cavalry.

The Commonwealth army retreated, abandoning the men in the right tabor who were left alone to defend it. Sadly, most were captured or killed. At the end of the day, nearly a third of the Commonwealth army was decimated.

Days of negotiation followed but failed, and Żółkiewski was left with no alternative but to pull back. In the next newsletter, I’ll describe how he employed a different configuration of the tabor for their retreat. Though its size and shape differed from the tabors employed in the battle, it proved highly effective in protecting the troops as they fled back to Poland. Despite its success, most would never see home because in the end it too failed, but not because of the concept or the formation itself. Instead, its undoing proved to be human nature.

Leave A Comment