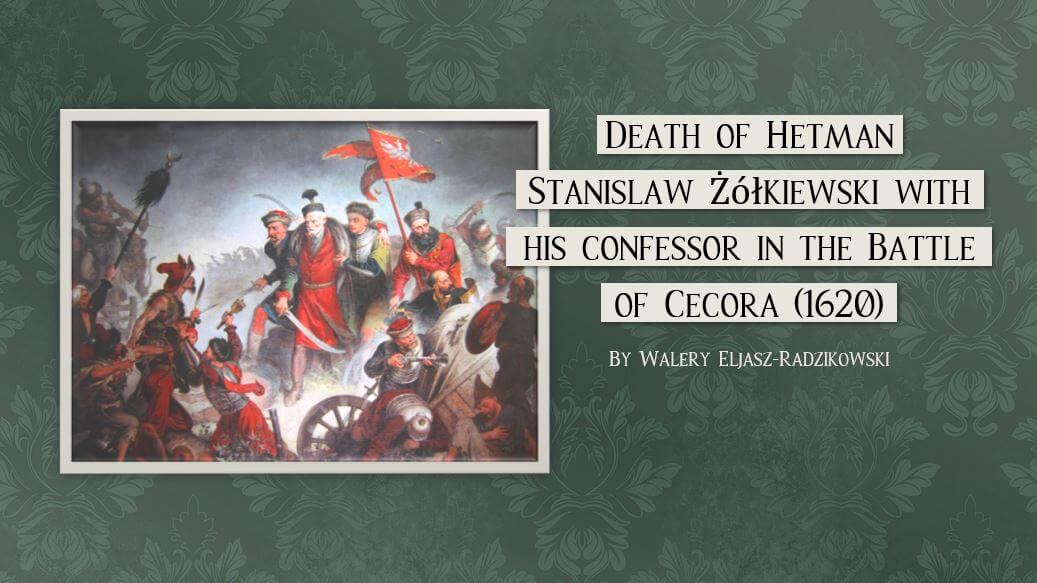

“I will fight till the end, and even after my death my dead body will stop foes from getting to my homeland.”

These words are said to have been spoken by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth’s Crown Grand Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski on the eve of his death. His demise came after the abysmal failure that was the Battle of Cecora in 1620.

While it’s not the focus of Book 3, the battle does figure into the story, so I had some studying to do. Before I dove into researching the history of the event and Żółkiewski’s final days, I didn’t realize what a tragedy it was. Sure, I had read about it, but the narrations were made up of a sentence here or a paragraph there. Sterile words on a page. As I dug deeper, though, the calamity that befell the Polish side began to breathe and come to life. And devastating doesn’t even come close to describing this ill-fated campaign.

The Commonwealth troops, led by the seventy-something Crown Grand Hetman (some sources say seventy-two, others say seventy-three), were woefully unprepared and undersupplied for the endeavor. Errors in judgment, strategy, and reconnaissance doomed the mission from the beginning. Plus, half the troops were comprised of colonel-magnates’ private armies, and I imagine it was a case of waaaaay too many cooks in a chaotic kitchen.

Each noble had his own agenda, and those conflicting interests compounded the problems undermining the campaign … though I can’t say I blame the magnates. While they were tromping through Moldavia with their troops, their lands lay vulnerable to attack by the roving Tatars. It had happened many times over the years, sometimes with disastrous results. One example was the Battle of Orynin in 1618. The Polish forces (again led by Żółkiewski and again made up of numerous private armies) clashed with Tatar troops and prepared for another assault the following day. That assault never came. Instead of engaging, the cunning Tatars bypassed the Poles and went north, pillaging and plundering Podolia—including those very magnates’ estates—with impunity.

But I digress. Back to the conflict in 1620: Consider that within the volatile mix of recalcitrant magnates and a mishmash of troops stood a once-heralded hetman who may or may not have been trying to redeem himself in his waning years. You see, he had lost favor with the king and his fellow magnates after the Orynin debacle. Cecora became the perfect storm that led to Stanisław Żółkiewski’s death.

When one reads about Żółkiewski and the Battle of Cecora, it’s easy to assume, as I did, that the great hetman died in that fight. I pictured him being slaughtered and beheaded (yes, he was beheaded) on the bloody battlefield by the Ottoman forces, but that’s not what happened. And the battlefield was actually east of Cecora—Cecora was the closest village, and hence the name was memorialized.

The actual battle took place on September 19 and pitted Polish forces against the Ottomans, under the command of Iskender Pasha, and the Tatars, led by Kantymir Murza. The result was an unmitigated disaster for the Commonwealth side. An innovative but poorly executed battle plan led to one-third of the Polish troops either being killed or captured on that day. The worst was yet to come, however. They withdrew to their camp, and a number of Poles tried to flee during the night. Some made it, but many died or were captured. The force was further depleted.

The Poles spent the following week negotiating, seeking a tolerable solution with Iskender Pasha. The effort bore no fruit, and Żółkiewski struggled to keep his demoralized troops in check.

Some historians assert the hetman merely went through the motions in negotiating with his counterpart. Among other concessions, there were talks of hostage exchanges and ransoms to be paid to the Turks, but the hetman had already decided that the price of a settlement was too steep … and not simply in gold. It’s been alleged that pride factored in as well: the notion of buying back his army was too humiliating for Żółkiewski. Capitulating would have been worse than retreating with his diminished force back to Poland and licking his wounds.

Finally the decision was made to pull out, and so they headed home on September 29, 1620, ten days after the battle. They began walking in a rolling stock formation, protected by rows of wagons fastened together. The Tatars harangued them, and so they took to marching at night, which further fatigued them. The Tatars also adopted a scorched earth strategy ahead of them, leaving the Poles without any forage. Their stores were gone, and their morale was at rock-bottom.

Utterly spent and without food, water, or horses, the beleaguered Poles marched at a pace of about seventeen miles each night, which is quite remarkable under the circumstances. But then they caught sight of Poland.

On Oct. 6, when they were within six or so miles from the border, what little discipline remained utterly fell apart. Disobeying commands, all but a few hundred scattered and ran for home. It didn’t end well: about half who fled made it. Had they stuck together, had they stayed in formation, they could have reached home soil.

The next day, October 7, Żółkiewski’s body was found. Though the Turks would take his head and send it to Sultan Osman II, mystery shrouds how he died and at whose hand. Circumstances aside, his was hailed a courageous death, so perhaps he did redeem himself in the end.

In all, only about two thousand out of nine thousand Commonwealth soldiers survived the campaign. Osman II, not quite sixteen years old, was buoyed by the crushing defeat his empire dealt the Commonwealth. In 1621, the sultan would muster another army to finish the job and “burn the Commonwealth to the ground,” but the tables turned, and his army was defeated. The young sultan was doomed to learn, too late, that his enemy was not ready to be vanquished. He too paid the ultimate price when he was murdered by his own janissarries less than two years later.

Today Cecora is known as Țuțora, Romania. According to Wikipedia, it is made up of several villages and has a combined population of just over two thousand souls. I wonder if the ghosts of the fallen Poles are counted in that number.

Leave A Comment