Polish Winged Hussars are often referred to as the shock troops of their day. Their main job was to break enemy lines, and they did so by charging in with their lances. Reports talk of them coming in at a full gallop, knee-to-knee, and it wasn’t unusual for the enemy to scatter in the face of the first charge. Typically, the hussars didn’t have to make more than one or two passes to smash that defensive line.

Other accounts say they slowed their horses just before impact, but honestly, I doubt the enemy paused to clock their miles per hour!

Another reason they were revered can be found in the many battles in which they were outnumbered by the enemy yet emerged triumphant, often with few casualties of either the human or equine variety.

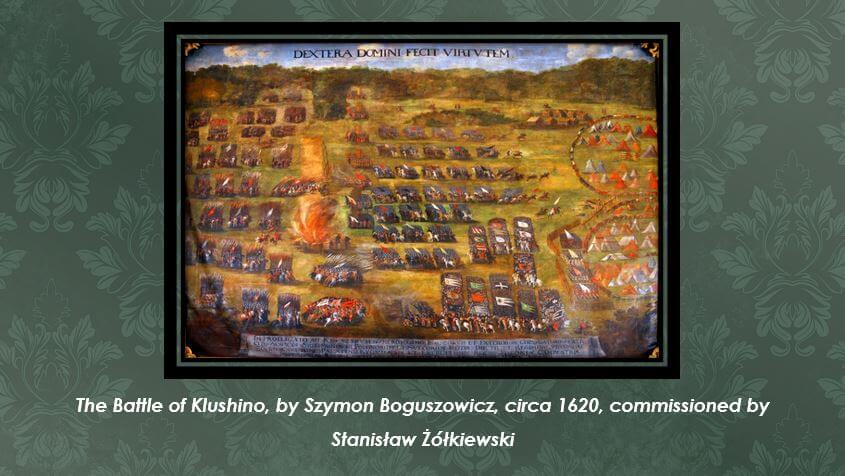

One famous example is the Battle of Kłuszyn, also known as the Battle of Klushino, which took place on July 4, 1610. There are differing accounts of the battle, but no matter which one you read, the odds were jaw-dropping.

In The Heart of a Hussar, the book opens on the battlefield at Kłuszyn. The narrative I chose to follow was that of Radosław Sikora, Ph.D, who is regarded as one of the world’s leading experts on the Polish Winged Hussars. In his paper, Battle of Kłuszyn (Klushino) 1610, Dr. Sikora asserts Crown Field Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski led a mere 2,700 men into battle against a force of over 48,000. More commonly found accounts report the enemy army at 35,000 (5,000 of which were mercenaries), and Żółkiewski’s force in the 6,500* range, with 5,500 being hussars. Even this number is staggering against a force of 35,000, but when one halves it to 2,700? Incredible!

Here’s how Sikora got to that number: First of all, it’s important to note that the Battle of Kłuszyn was part of the bigger military operation that was the Polish siege of Smolensk, which had been going on since 1609. The Russians had teamed up with the Swedes and sent troops to rescue Smolensk. Upon hearing of the troop movement, Żółkiewski set out to meet up with additional Polish regiments in Carowa-Zajmiszcze, leaving Smolensk in early June, 1610, with 2,080 cavalry, 1,100 infantry, and 100 Cossacks. According to Sikora, these numbers were “on paper,” and the actual numbers would have been 10% less for cavalry, assuming everyone being paid was present. Battle casualties, disease, desertion, and other vacancies could drive those numbers even lower.

Before he could reach Carowa-Zajmiszcze, Żółkiewski received word that the Polish garrison at the captured Muscovite fortress in Biała (Bely) needed help as the Muscovites were planning to recapture it, so he detoured there instead. Hearing of his approach, the Muscovites withdrew and battle was averted. Nonetheless, Żółkiewski divided his troops at Biała, sending some back to Smolensk and leaving some to bolster the garrison at the fortress. With his depleted force, Żółkiewski departed Biała for Szujsk, a staging area with a high concentration of Polish troops. Here he added more troops to his number (it’s estimated he had between 15,600 and 18,600 total, though half were camp followers), and they set out once more for Carowa-Zajmiszcze.

At Carowa-Zajmiszcze, Żółkiewski once again divided his troops, leaving behind camp followers and less seasoned soldiers and taking with him 2 guns and his elite troops. The latter consisted of 3,080 hussars, 850 light Cossack cavalry, 100 Petyhorcy cavalry (light cavalry who carried shorter, lighter lances than the hussars’ kopie), and 200 infantry, but bear in mind these were the numbers “on paper.” Taking into account the usual 10% reduction from “on paper” to “actual,” this leaves a tally of approximately 3,600 cavalry and 200 infantry, for a total that’s a fraction below 4,000. And this is the number most frequently found in Polish sources.

Against 35,000.

Yes, my jaw dropped when I first read this. However, the picture becomes even more amazing when one takes into account Samuel Maskiewicz, a hussar who was present at the battle. Maskiewicz stated the cavalry actually numbered 2,500, which meant that together with infantry, the total number of Polish troops was 2,700. More staggering is that at the time of battle, Żółkiewski estimated the enemy troops at 35,000, but several years later, as he detailed the battle in his writings, the count escalated to 48,000: 40,000 Muscovites (including camp followers, many of whom fought with the soldiers) and 8,000 foreigners.

This made the odds 2,700 against 48,000. And the hussars won.

As for the battle itself, more on that in another newsletter, but I’ll leave you with this: I predict more jaws will drop.

*This number was quite possibly derived from a troop count before Żółkiewski divided his army.

Leave A Comment