- The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth came about as the result of the Treaty of Lublin, signed in 1569, which united the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. The Commonwealth was one of the richest, most powerful, and most populous countries in Europe at the time. It existed until the Third Partition of Poland in 1795.

- Poland was one the great powers and a center of culture in Eastern and Central Europe for two hundred years. Memories of its former greatness were methodically erased during the Partitions of Poland in the eighteenth century. Russia, Austria, and Prussia carried off Poland’s books and treasures and disseminated propaganda that its might and influence had never existed.

- Golden Freedom, or Golden Liberty, refers to privileges enjoyed by the Polish nobility (the szlachta). It conveyed religious freedom and declared all nobility equal, regardless of rank or status. It also gave the nobility extensive legal rights, including assigned private jurisdiction, protecting them from being arrested or having their property seized without a conviction from a court of law. In addition, it limited the monarchy’s power. The szlachta made up the two-chamber legislature/Parliament: an appointive Senate and an elected Sejm. The king was chairman of the Senate. The szlachta filled the legislative seats, wrote the laws (often for their benefit), and elected the king. In short, they wielded a great deal of power. The Liberum Veto conveyed the power of veto on a single member so, quite literally, one man could bring voting to a halt.

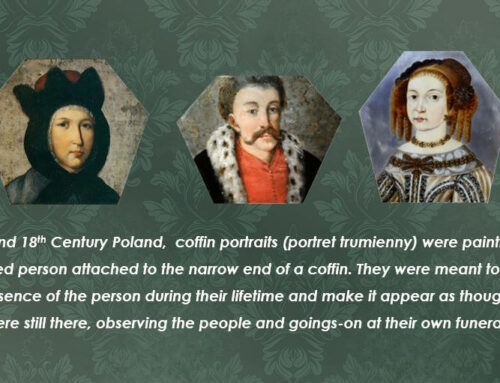

- With the advent of the Golden Liberty, formal titles were banned. All noblemen were to refer to one another as “Pan” (“Sir” or “Lord”), whether they were a lowly noble or a powerful magnate. Loopholes did exist, however. For instance, noblemen who signed the Union of Lublin with their titles were allowed to keep them.

- Noblemen were granted the right to bear coats of arms. However, coats of arms worked a little differently in the Commonwealth. Noble families adopted those belonging to others, fitting themselves under an “umbrella,” if you will. While there were over forty thousand noble families, there existed approximately seven thousand coats of arms (and variations). Thus it wasn’t uncommon for two noble families to share the same coat of arms.

- During the time the novel takes place, Poland was fighting Muscovy, Sweden, and the Ottoman Empire. The conflict with Sweden was a series of intermittent wars that spanned two centuries. King Zygmunt III Vasa was Swedish and had been King of Sweden until his uncle, Charles IX Vasa, who had been ruling in Zygmunt’s place, took the crown for himself. Zygmunt was deposed in 1599 but never gave up his claim to the Swedish throne.

- At times, Poland was allied with Sweden against Muscovy, and at other times with Muscovy against Sweden. For instance, Poland and Sweden signed a truce in 1611 that lasted until 1617, when full-on war broke out again between the two countries over, among other things, possession of Livonia and domination over the Baltic Sea.

- The conflict with Muscovy arose during Russia’s Time of Troubles (1598-1613), when that country was in the midst of a leadership crisis. The conflict has several names, including the Dymitriads, the Polish-Muscovite War, the Polish Invasion, and the Polish Intervention. The conflict ran from 1605 to 1618, though Poland’s real involvement began in 1609 when Muscovy and Sweden signed a treaty, with Sweden pledging some of its military force to Muscovy. Poland had been seeking to federalize Muscovy and saw this union as a threat. The King of Poland acted, marching on and besieging Smoleńsk with a small army. The Commonwealth would eventually take Smoleńsk in 1611. Poland did take Moscow in 1610, occupying it until 1612. The king’s son, Prince Władysław, was elected tsar by the boyars in 1610, but the king sought to change the terms of the agreement with Muscovy, and the boyars became alarmed. The agreement unraveled, Władysław did not take the throne, and the conflict continued.

- To the south, the Ottomon Empire and its vassals, the Crimean Tatars, threatened the Commonwealth and Christianity. The Commonwealth was often referred to as the “Bulwark of Christendom,” and indeed was a deciding factor in turning the Ottomans back when they were set to capture Vienna in 1683. Of the two, the Tatars were deemed the greater threat because they raided annually, pillaging, burning, and carrying off countless captives to be sold in Turkish slave markets. It is estimated that in all, the Tatars took over one million Poles captive. Their raiding was equally, if not more, devastating in surrounding countries, such as Muscovy.

- The Moldavian Magnate Wars were a series of conflicts spanning from the late sixteenth century to the early seventeenth century. Amid ongoing cross-border raids by Cossacks into the Ottoman Empire on one side and Tatar raids into the Commonwealth on the other, a semi-permanent war zone existed. In this hotbed, magnates from the Commonwealth began interfering in Moldavia’s affairs in order to extend the Commonwealth’s influence, which upset the Ottoman Empire. Wallachia, Transylvania, Hungary, and the Habsburgs were also part of the mix. Stefan Potocki, a powerful magnate, sought to re-establish the head of Moldavia and led an army of seven thousand into battle against Moldavia and the Ottoman Empire. He was defeated in July 1612 and taken prisoner. He later died a captive in the notorious Fortress of the Seven Towers (Yekidule Fortress). Months after Potocki’s defeat, Żółkiewski negotiated a treaty without further bloodshed. However, the conflict would continue until the Battle of Cecora in 1620, where Żółkiewski lost his life.

- The Thirty Years’ War began as a war over religion. The conflict lasted from 1618 until 1648 and involved the Holy Roman Empire and nearly all of Europe. For the most part, the Commonwealth stayed out of it, aiding the Holy Roman Empire indirectly. For instance, Zygmunt III sent ten thousand cavalrymen to help the Habsburgs. A number of hussars, perhaps adventurers, are said to have joined the fight on the side of the Holy Roman Empire, hiring on as mercenaries. Sweden’s engagement overlapped its war with the Commonwealth, teaming up with Muscovy, who sought to recover Smoleńsk.

- Biała (also known as Bely) was a fortress where a Polish garrison came under attack in the weeks prior to the Battle of Kłuszyn. Żółkiewski was marching his troops to Carowa-Zajmiszcze when he diverted to rescue the garrison. Biała was one of the locations where he divided his already small force prior to the battle.

- Carowa-Zajmiszcze was the location where the vanguard of the Muscovite army was garrisoned, and it was here Żółkiewski traveled after leaving Biała. The Muscovites withdrew the week prior to the Battle of Kłuszyn. When Żółkiewski received news of the approaching Swedish-Muscovite army, he further divided his troops and marched his small force from Carowa-Zajmiszcze to the battlefield near Kłuszyn.

- The main character, Jacek Dąbrowski, is promoted and replaces his slain lieutenant in the first book, making Mateusz Zalewski his immediate superior. Mateusz is the captain, but he would have actually been the lieutenant (the porucznik), and Jacek would have become deputy or second lieutenant. In the second book, Jacek becomes the captain, and again, would have actually been the porucznik, while his friend and subordinate, Henryk Kalinowski, became the deputy or second lieutenant. Hussars did not use ranks that translate to those we are accustomed to. Since they were all equals, they were all designated “junior officers” under their commander (the rotamaster or rotmistrz). For the sake of facility, the designations of lieutenant, captain, and colonel (pułkownik) have been applied to this story.

- There were two top generals in Poland: the Crown Grand Hetman and the Crown Field Hetman, with the Crown Grand Hetman being the highest ranking of the two. Both were offices assigned for life. Lithuania had its own separate, equivalent designations for generals.

- The main character fights with a nadziak, a war hammer with a hammer head on one side, and a claw on the other (also known as a horseman’s pick). The distinctive term “nadziak” wasn’t yet established at the time this novel takes place. It might have been called a “czekan,” which was a catch-all term for war hammers. Later, the term czekan would be used to distinguish a war hammer with a hammer head on one side, and an ax blade on the other.

- The layout of Biaska Castle is loosely based on Ogrodzieniec Castle in the Eagles’ Nests fortifications in the Polish Jura. Its geographical position would, however, more closely resemble that of Bobolice Castle.

- The Eagles’ Nests fortifications are a series of castles along Poland’s western border that King Kazimierz the Great (Kazimierz III Wielki) ordered built in the fourteenth century to secure Poland’s western border against its aggressors. As time went on, the fortifications were no longer necessary, and many fell into disrepair.

- Twierzda is loosely based on Kudryntsi Castle, which was not built until the early 1600s.

- Hetman Żółkiewski was likely not in Podolia in the spring of 1611. His memoirs place him in Mogilev, Moscow, and Smoleńsk.

- Placing Hetman Żółkiewski at his home during Christmas 1612 is merely my supposition. He was, however, in the area in October of 1612 when he negotiated a treaty with Stefan Tomża of Moldavia at Chocim. Likewise, King Zygmunt III’s presence in Warszawa, after departing Muscovy, is supposition. Jacek’s friend in these scenes, Magdalena von Rohan, is a fictional character.

- The tale of the Cossacks penning the letter to the Sultan is real, although it’s thought to have been written in the mid-1600s. Interpretations of the Sultan’s letter to the Cossacks, and their reply, can be found on line and are quite entertaining to read.

- Women were indeed money lenders, most popular in Gdańsk, where they loaned funds to merchants and businessmen.

- The Tatar commander, Bater Beg, was a real commander who led tens of thousands of Tatars into Russia in 1614. His real name was Bogatyr Giray Diveev, and Bater Beg was the name the Polish used for him.

- Khadjibey is the present-day port city of Odessa in southern Ukraine. The notion that slave trade took place there is purely the author’s invention.

- The story of Jacek’s escape from the Cesaret is based on the real-life tale of a Polish nobleman, Marek Jakimowski, who was captured by the Ottomans at the Battle of Cecora in 1620. He was sold into slavery and bought by an Ottoman admiral and governor, Kassym Beg. Marek served aboard Kassym Beg’s lead galley in a fleet of four merchant ships. His adventure was first printed in Rome in the 1600s, then in several other countries and languages.

- Maływieża is loosely based on Mirów Castle, a watchtower one mile from Bobolice Castle. The two are located in the Eagle’s Nest fortifications and are said to have been connected by a tunnel. The tale of the twin brothers, the treasure, the witch, the girl, and the “White Lady” is based on a ghost tale about Bobolice and Mirów.

- Miles used are English miles, not Polish miles, which were longer.

- The novel uses a variety of English and French terms. While perhaps not historically accurate for the story’s place and time, I chose terms I felt would be easily recognizable to the modern reader.

- A number of historical locations and figures were referred to by different names and had various spellings. Where possible, I opted for names recognizable today, in their Polish spellings.

- In my research, I discovered many rich Polish Christmas customs and traditions, though not all are incorporated in this story. I also found a variety of references to the number and types of dishes served at Christmas Eve supper (Wigilia). I chose a historical source which stated that an uneven number of dishes were typically served. In wealthier homes, that number ranged from eleven to thirteen, which is why thirteen were served at Biaska, the fictional castle in this novel.

Leave A Comment