There was a period in the 17th century, during Muscovy’s Time of Troubles, when the Commonwealth of Poland-Lithuania seemed to have its enemy to the east collared. For years, the Commonwealth had been annoyed by Muscovy, engaging in the occasional tussle, but not full-scale war. However, when Muscovy aligned militarily with Sweden, one of the Commonwealth’s major enemies, Poland’s King Zygmunt III decided to act: he invaded.

This move was not popular with the Sejm, Poland’s parliamentary house. In fact, they didn’t back their king. But Zygmunt was determined, and he proceeded with his war against Muscovy, starting with the siege of Smolensk in 1609. The siege would last two years, and Poland finally prevailed when Smolensk fell in 1611.

In the meantime, Poland won a great victory in July 1610 at the Battle of Kłuszyn in a decidedly lopsided contest, where Grand Hetman Stanisław Żółkiewski led a small group of winged hussars against a Muscovite army eight to nine times larger (this battle is the opening scene of The Heart of a Hussar).

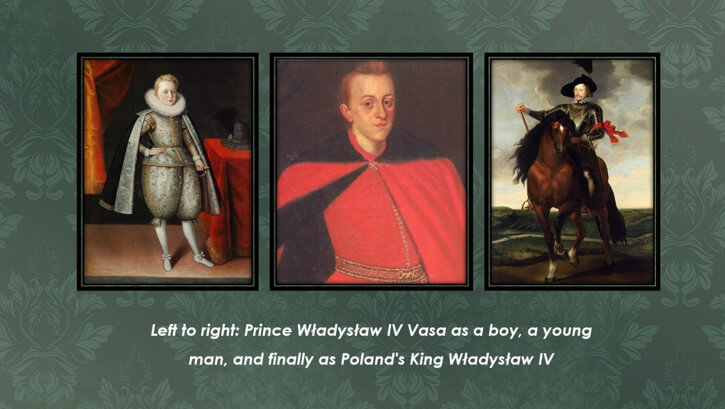

Żółkiewski endures as one of Poland’s most brilliant military men. He was also a gifted diplomat, and when he led his force into Moscow in the summer of 1610 after the Battle of Kłuszyn, he was able to broker a pact with the boyars who elected fifteen-year-old Prince Władysław IV Vasa the Tsar of Muscovy.

Władysław would never ascend to the throne, however, because his father balked at one of the conditions of the agreement, namely that his son convert to Orthodoxy. For all of Poland’s religious tolerance, King Zygmunt was a staunch Catholic who harbored ambitions of converting all of Muscovy to Catholicism. Thus began the unraveling of the pact. The incident prompted Żółkiewski to pen Expedition to Moscow, a memoir that explains his side of the story.

Before Żółkiewski left Moscow that summer, he installed a garrison in the Kremlin. A year later, in July 1611, the Poles came under siege as the result of an uprising by Moscow’s population. Several attempts were made to lift the siege, including one by another accomplished Polish general, Hetman Jan Carol Chodkiewicz, but none were successful. The starving garrison finally surrendered in November of 1612. There are narratives that describe a slaughter as the surviving Polish soldiers exited the Kremlin–some say as many as half the survivors were killed. In modern Russia, the day is commemorated on November 4 as the Day of National Unity .

I often wonder what a Polish-led Muscovy would have produced. Could the Commonwealth have held on to such a vast territory? It’s an intriguing idea for an alternate history tale.

Leave A Comment